As we come to the end of September, I wanted to share a couple of posts I’ve written for the University of Missouri’s Partners in Prevention regarding suicide education and prevention. Immediately below are quick titles and links to each or further, previews of each with accompanying links to the full posts.

Suicide Prevention Quick Links:

- “Suicide Prevention Week – Increasing Our Compassion and Understanding”

- “The National Suicide Prevention Line is Now 988!”

- “Coping with Loss by Suicide”

Suicide Prevention Article Previews:

“Suicide Prevention Week – Increasing Our Compassion and Our Understanding”

The beginning of September marks Suicide Prevention Week, giving us a focused opportunity to learn and think compassionately about suicidal ideation (thoughts of suicide), suicide attempts, and those we have lost. In the spirit of compassion, I wanted to take a moment to highlight some numbers and then, move in for a close-up view of “humanity behind suicide” to hopefully help us engage a little more personally, bravely, and effectively in prevention efforts.

In the way of numbers, suicide is one of the most common forms of death in the US, marking it as a major public health crisis. While it is the 10th leading cause of death overall, it is the 2nd leading cause in the 10-34 age range, and 4th in the 35-44 age range (CDC, 2019). These numbers translate to nearly 47,500 lives lost each year, making it extremely likely that you or someone you know has been impacted by suicide.

When we encounter someone experiencing suicidal thoughts, it can be very difficult or even intimidating to talk about. And yet, it is actually getting closer to the “humanity behind suicide” that can help us be more comfortable and willing participants in prevention efforts. In my years as a therapist on a college campus, I went through suicide prevention training countless times. However, it was the students I had the privilege of helping who made the training more “human.” I’m hoping some of what I learned may help you also as we work to keep our students safe. (Details generalized or altered to protect student privacy.)

- The majority of students I worked with did not necessarily want to die, but they couldn’t see how to keep living. This wording may sound like semantics, but it’s not. One of the primary influences behind suicide is a sense of hopelessness that one’s situation cannot or will not change. Understanding that some people are thinking about dying because they are struggling to keep on living can help us focus our efforts on hope, seeking solutions, and encouraging the person to pause their planning. Any space we can put between the crisis they are experiencing and the act of suicide is a space where a life can be saved.

To read the full post, link here.

“The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is Now 988!”

With Suicide Prevention month coming up in September, we are excited to discuss a public policy advancement in suicide and crisis intervention. In April, at Meeting of the Minds, many of us had the privilege of attending a discussion around the national change from the previous 1-800 number for the Suicide Prevention Lifeline. This change is designed to make mental health crisis care more accessible, easier to remember, and use several fiscal and human capital resources more efficiently. That change is known as 988.

How Did This Happen?

In July 2020, while the world was reeling from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) approved the shorter, more easily memorized “988” as the new number for the National Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. Within two years, telecommunication companies were instructed to make the changes necessary to make sure 988 would be accessible to all users via call, text, or chat services at https://988lifeline.org

Why Make the Change?

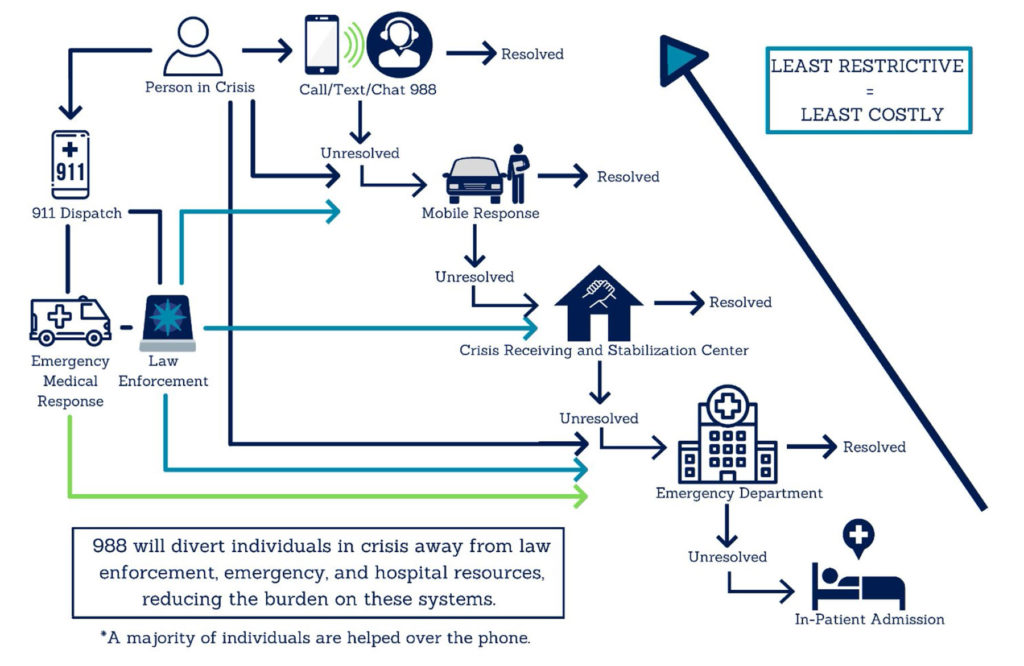

As mentioned, 988 is easier to remember than the previous 1-800 number, a valuable asset for someone facing a mental health crisis. However, this more focused and streamlined approach is not just about remembering a phone number. Instead, the entire process previously followed during a mental health crisis was recognized as being inefficient.

For far too long, most people in a mental health crisis had few options, often needing to call law enforcement and wait at a hospital for an assessment. Despite hospital best efforts, this process would often take hours while the person in crisis sat awaiting treatment, and law enforcement officers could not return to their duties.

So, How is 988 Different?

When a person calls 988, they are connected to a local* suicide prevention specialist trained to help navigate a “no wrong door integrated crisis system” of care. Depending on the crisis, this may include someone to talk to, someone to respond, and/or somewhere to go. In Missouri, rather than being taken directly to the hospital, the following options are now potentially available:

To read the full post, link here.

“Coping with Loss by Suicide”

Suicide Prevention Month comes with a lot of public health information on suicide prevention as well as statistics and education about new resources aimed at reducing the incidence of suicide. However, despite best efforts, sometimes we still lose people. As the twelfth leading cause of death in the general population, the second for people aged 10-14 and 25-34, the third for 15-24-year-olds, and fourth for those 35-441, as well as a significant risk for middle-aged men and the elderly, it is likely that you or someone you know will be impacted by a loss by suicide.

Those who lose someone they care about to suicide are often referred to as suicide “survivors.” While losing someone you care about for any reason is challenging, a loss by suicide can carry with it unique, complicated grief. If you or someone you know loses someone to suicide, this information may help you cope.

Suicide Often Results in Complicated Grief

One of the most difficult parts of a loss by suicide is the shock that accompanies the loss. For those who have seen Alice in Wonderland, the scene where Alice falls down the rabbit hole and everything is upside down, confusing, and disorienting, is a good mental picture of the way the world seems to lose its mental “footing” during this type of loss and shock.

Because our brains do not like to feel so disoriented and ungrounded, people tend to respond in one of a couple of ways to initially cope with a loss by suicide. The first, as mentioned, is shock which may play out as feeling numb or detached. When someone experiences trauma (which loss by suicide can be) numbness can protect the mind from overwhelm. On the flip side, some survivors experience intense emotions like anger or sadness that may feel like they come in “waves” as they attempt to process the loss.

Similarly, some people experience denial, feeling as though they aren’t affected while their brain takes time to process the information. It is not uncommon for some people to have a delayed reaction to loss by suicide until they have time to analyze the loss and emotions.

Because our brains want to make sense of things that are disorienting, many survivors struggle with guilt or a strong desire to understand “why” the loss happened. These thoughts can feel almost obsessive, taking up a large portion of a survivor’s thinking as they attempt to understand how this loss could have been prevented and/or want to understand everything they can about what the person they lost was feeling, thinking, etc.

Risks and Challenges Associated with Loss by Suicide

A loss by suicide has unique risks and challenges. One of the most difficult is that the concept or act of suicide has a complicated historic relationship with morality, religion, personal or family image, etc. While we know that suicide is a mental health crisis that deserves compassion and understanding but, for some, the stigma remains. It is important that those who lose someone to suicide find support from people who are compassionate toward this type of loss, rather than critical or shaming.

To read the full post link here.